A file system handles the persistent storage of data files, apps, and the files associated with the operating system itself. Therefore, the file system is one of the fundamental resources used by all processes.

In linux, everything is represented as a file, including hardware devices, system information, and inter-process communication channels.

Looking at File Systems

There are two ways to look at the implementation of file systems:

- Data Structures

- What types of on-disk structures are utilized by the file system to organize its data and metadata?

- Access Methods

- How does the file system provide access to its data and metadata?

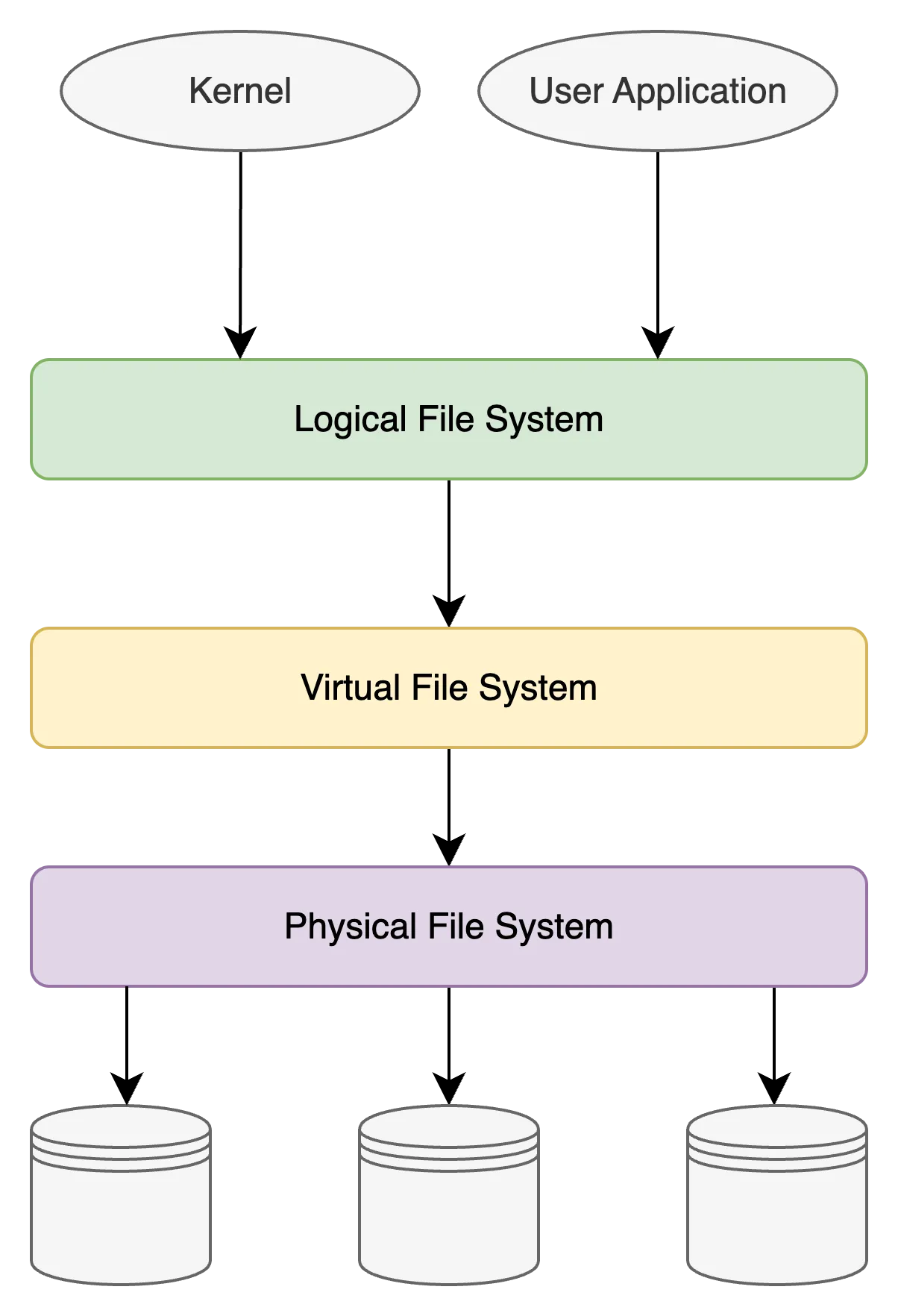

Linux File System Structure

Logical File System

The logical file system acts as the interface between user applications and the file system itself. It serves as the user-friendly front-end system, ensuring that applications can interact with the file system without needing to understand its internal workings.

Virtual File System (VFS)

The VFS is an abstraction layer that provides a standardized interface so that different file systems can coexist and operate seamlessly within the same operating system. It abstracts the details of various file systems, allowing applications to access files in a uniform way regardless of the underlying file system type.

Physical File System

The physical file system is responsible for the tangible management and storage of physical memory blocks on the disk. It handles low-level details of storing and retrieving data, including managing disk blocks, inodes, and directories. It also ensures efficient allocation and utilization of the physical storage resources.

Inodes

Inodes are data structures that store metadata about files and directories in a Unix-like file system. Each file or directory is associated with an inode, which contains information such as:

- File type (regular file, directory, symbolic link, etc.)

- Permissions (read, write, execute)

- Owner and group IDs

- File size

- Timestamps (creation, modification, access times)

- Pointers to the data blocks where the actual file content is stored

When a file is created, the file system allocates an inode for it and assigns a unique inode number. The inode number serves as an identifier for the file within the file system.

Address Translation: Logical vs. Physical

From an application’s perspective, a file is simply a sequence of bytes. But on disk, that same file is scattered across physical blocks. The file system provides the critical service of address translation: mapping logical file offsets into physical disk blocks.

- Logical address: the byte offset within the file.

- Physical address: the actual location on disk.

Modern file systems use extents to record these mappings. Instead of storing a pointer for each block, an extent describes a run of contiguous blocks:

Logical offset 0 → Physical block 1000 (length = 8192 bytes)Logical offset 8192 → Physical block 9000 (length = 4096 bytes)This mapping allows efficient reads/writes and helps avoid fragmentation, and is done by the Memory Management Unit (MMU).

Comparison between Logical and Physical Addresses

| Aspect | Logical Address (File Offset) | Physical Address (Disk Block) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Position of a byte/segment within a file (what apps see). | Actual location of data on storage device (what disk sees). |

| Viewpoint | User-space / application perspective. | Kernel / device perspective. |

| Representation | “Byte 8192 of file.txt” | “Block 123456 on disk partition /dev/sda1” |

| Mapping Unit | Sequential bytes (stream-like). | Fixed-size blocks (commonly 4 KB). |

| Who Uses It | Programs, system calls (read(), write()). | File system drivers, block I/O layer, storage devices. |

| How It’s Resolved | Inode → extent mapping → physical location. | Direct block number/index on disk. |

| Visibility | Visible to applications and APIs. | Hidden from applications; only visible via tools (e.g., FIEMAP, filefrag). |

| Example | Offset = 8192 bytes | Block = 12345 (sector range 98765–98776 on disk) |

Sparse Files

Imagine you create a file and write data at the beginning 100 bytes, then you skip ahead 1 GB and write another 100 bytes. The file system does not need to allocate physical blocks for the entire 1 GB gap. Instead, it can create a sparse file where only the written regions consume disk space.

These unmapped regions treated as logical “holes.” These holes are filled with zeroes when read, but do not occupy physical storage.